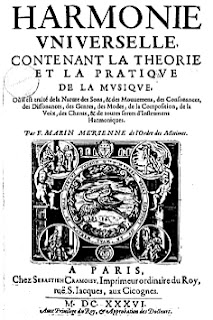

Marin Mersenne (1555-1648) foi um teólogo, padre, filósofo, matemático e teórico musical nascido na França. Foi uma figura importante para a divulgação da produção científica e filosófica de sua época, uma vez que ele mantinha correspondência com vários pensadores importantes daquele tempo, dentre eles Descartes, Galileu, Pascal e Torricelli. No campo da música, sua maior contribuição foi o tratado intitulado "Harmonie Universelle". Publicado no ano de 1636, o "Harmonie" trata sobre vários aspectos práticos e teóricos da música do século XVII, funcionando como uma grande enciclopédia voltada para o assunto. Nesta postagem, tratarei dos verbetes relacionados à flauta transversal e à flauta doce contidos na obra em questão.

Flauta transversal ("Fluste d'Allemand")

O verbete que fala sobre a flauta transversal declara ter como propósito fornecer informações sobre a "Fluste d'Allemand" (se o leitor se recorda bem, a flauta transversal daquela época era conhecida na maioria dos países europeus como "flauta alemã" - ver postagem sobre a flauta na Idade Média). Mersenne escreve sobre as medidas da flauta, além de falar sobre seus princípios básicos de funcionamento: como segurá-la e como conduzir o ar para dentro dela, trazendo também uma tablatura de dedilhados para a produção das notas.

Antes mesmo de começar a falar sobre a flauta transversa, o autor se preocupa em deixar claro que esse tipo de flauta é diferente de um instrumento conhecido como "Flageollet" (em algumas publicações grafado com apenas um "L" no lugar dos dois "L's"), cuja versão francesa, por sua vez, é bastante semelhante à flauta doce:

Esse é um flageolet inglês. Seu som é bem próximo àquele de um tin whistle irlandês.

No vídeo acima, uma demonstração de um "flageolet duplo", o qual se assemelha mais ao modelo inglês de flageolet. Note que o som parece estar entre o som da flauta doce e do tin whistle irlandês (ver postagem sobre os diversos tipos de flauta).

A imagem acima pertence à publicação de Mersenne. As letras e números nela contidos servem para orientar o leitor: "Mesmo que algumas pessoas costumem colocar esse tipo de flauta na categoria do Flageollet por conta deste ter, assim como ela, seis orifícios a serem tapados, preferi colocá-la à parte pelo fato de que a embocadura não se encontra na região A B como acontece nas demais, mas sim no orifício I (...). A embocadura é feita colocando o lábio inferior na borda do primeiro orifício e empurrando o ar bem suavemente para dentro dele.". O autor defende que a embocadura da flauta transversal é bem mais difícil de ser aprendida do que a embocadura das flautas semelhantes ao flageolet.

Mersenne fala um pouco sobre quais materiais poderiam ser utilizados para fabricar flautas transversais. O material mais usual era a madeira, variando, preferencialmente, entre a do pé de ameixa e da cerejeira. O ébano também poderia ser utilizado. Além da madeira, poderiam ser usados o cristal e o vidro, mas exemplos de flautas nesses materiais são bem mais raros. Ainda falando sobre aspectos físicos da flauta, ele fornece uma série de medidas para os diâmetros dos orifícios, para as distâncias entre eles e para o diâmetro de seu tubo. Ardal Powell, em seu "The Flute", porém, argumenta que há algumas falhas nas medidas dadas: Mersenne fala de uma flauta supostamente afinada em sol, mas a extensão dada pela tablatura de dedilhados parece remeter a uma flauta em ré, enquanto que a distância dada para o espaço entre os orifícios da flauta não corresponde a nenhum dos dois instrumentos. A propósito, a tablatura de dedilhados presente no verbete serve também àquele que toca pífano ("Fifre"). Segundo o autor, ele e a flauta transversal são dois instrumentos extremamente semelhantes, diferindo apenas em sonoridade (a sonoridade do pífano sendo mais estridente e viva) e não em técnica.

Flauta doce ("Fluste d'Angleterre")

O verbete que fala sobre a flauta doce tem como proposta informar o leitor sobre a "Fluste d'Angleterre" (flauta da Inglaterra), também conhecida como "Fluste douce" (flauta doce) e flauta de nove orifícios. Ficou conhecida pelo primeiro nome por ter sido enviada à França por um rei inglês cujo nome não é citado no verbete; pelo segundo nome por conta da doçura de seu som; pelo terceiro nome pelo fato de possuir nove orifícios. Atualmente, é também conhecida entre os franceses como "flûte à bec" (flauta de bico).

A flauta descrita por Mersenne poderia ser tocada tando por destros tanto por canhotos, uma vez que o orifício mais próximo do pé da flauta era dobrado (um furado mais à direita, outro furado mais a esquerda, mas ambos na mesma altura e com o mesmo diâmetro), a fim de que os dedos mínimos das mãos de ambos os tipos de flautistas pudessem alcançá-los. Além disso, ele afirma que a extensão da flauta doce é a mesma extensão do "Flageollet". Conforme a tablatura mostrada por ele, a extensão aproximada seria equivalente a uma décima quinta.

A imagem acima está presente no verbete. Ela mostra vários instrumentos musicais, a maioria deles flautas doces. As letras presentes na imagem servem para que o leitor se localize ao procurar nela as partes dos instrumentos às quais Mersenne faz menção. O instrumento apontado pela seta verde é a flauta doce em sua forma mais conhecida. As setas azuis mostram uma flauta doce menos conhecida. Segundo o autor, tal flauta poderia medir de 7 a 8 pés de comprimento (algo entre dois metros e dois metros e meio!). A elipse azul mostra a peça central da flauta e o orifício escondido por ela, o qual é tapado através da ação de chaves. Em flautas menores, tal orifício é dobrado (conforme descrito um pouco mais acima nesta postagem). Aqui, porém, as chaves que tapam esse orifício são colocadas em ambos os lados da flauta. No vídeo abaixo você poderá ver melhor como funciona e como soa esse instrumento. Para ver outros tipos de flauta doce, visite a postagem referente aos diversos tipos de flauta, presente neste mesmo blog.

Esse verbete traz algumas linhas muito curiosas sobre uma técnica cujo emprego só se faz, atualmente, em música contemporânea e popular. Mersenne comenta com muita naturalidade que a extensão da flauta doce pode ser expandida se o flautista tocar e cantar ao mesmo tempo, "pois o vento que sai da boca enquanto se canta é capaz de fazer a flauta soar, de forma que um homem sozinho pode fazer um Duo". É interessante o fato de que, no verbete voltado para a flauta transversal, tal técnica não foi mencionada. O autor fala apenas sobre a possibilidade da construção de instrumentos dotados de dois tubos, invenções que capacitariam o instrumentista a fazer um duo sem precisar de outro músico para acompanhá-lo. Talvez o autor não tivesse visto em sua relativamente longa vida alguém que fosse capaz de aplicar tal técnica à flauta transversal com a mesma eficiência aplicada à flauta doce, levando-o a crer que o canto interferiria de forma drástica na embocadura necessária para tocar o tipo mencionado de flauta. Não obstante, é realmente notável que, em 1636, alguém já havia escrito sobre algo cuja entrada no repertório técnico flautístico se deu numa época relativamente recente!

Principais fontes:

MERSENNE, Marin. Harmonie Universelle. Paris: 1636. Fac-símile presente em: SAINT-ARROMAN, Jean. Méthodes & Traités: Flûte à Bec - Europe 1500-1800. Vol.I. p.165-168. 3ªEd. Bressuire: Anne Fuzeau Productions, 2001.

MERSENNE, Marin. Harmonie Universelle. Paris: 1636. Fac-símile presente em: SAINT-ARROMAN, Jean. Méthodes & Traités: Flûte Traversière - France 1600-1800. Vol.I. p.7-10. 3ªEd. Bressuire: Anne Fuzeau Productions, 2001.

POWELL, Ardal. The Flute. New Heaven and London: Yale University Press, 2002.